HEARING THROUGH WIRES: The Physiophony of ANTONIO MEUCCI

by Gerry Vassilatos

ARRIVALS

Antonio Meucci is the forgotten and humble genius whose inventions precede every revolution in communication arts which were achieved during this century. The time frame during which his notable discoveries were made is a most remarkable revelation. How Meucci developed his accidental discoveries into full scale working systems is a true wonder in view of this time reference.

The culturing of technology from the simple sparks of vision is a feat of its own distinct kind. As the earliest chronicled inventor of telephonic arts he is justly applauded as the true father of telephony by afficionadi who know his wonderfully touching biography. But he invented far more than the telephone with which we are familiar. Meucci discovered two separate telephonic systems. His first and most astounding discovery is known as physiophony, telephoning through the body...hearing through wires. His second development was acoustic telephony, preceding every other legendary inventor in this art by several decades.

Meucci powered telephones with electricity taken from the ground through special earth batteries, and from the sky by using large surface area diodes to draw static from the air. Eliminating the need for employing batteries in his telephonic systems, Meucci first conceived of a transoceanic vocal communication system. His notion was grand and achievable. Marconi later employed methods pioneered by the forgotten Meucci.

He developed ferrites, with which he constructed true audio transformers and loudspeaking transceivers. He invented marine ranging and undersea communication systems. His numerous achievements in chemical processing and industrial chemistry are too numerous to mention in such a brief treatise. All of these wonders were conceived and demonstrated well before 1857.

Sr. Meucci was a prolific inventor, engineer, and practical chemist. Living in Florence, he worked as a stage designer and technician in various theaters. Antonio Meucci and his wife left Florence to flee the violence of the civil insurrections which raged throughout Italy. Many immigrants who wished for a peaceful life thought they might find some measure of solace in the New Land which lay to the west.

Unhappily restricted by law from entering The United States, persons such as Meucci and his family chose the route into which most other Mediterraneans were forced at the time. Being turned southward, they were literally compelled to dock in Caribbean or South American ports. There sizable populations of European immigrants remain to this day, legally restricted from North American shores. Most found that their presence there was received with an acceptance and warmth equal to a homecoming. It should have been in these lands that their legacies were written.

New arrivals in Cuba, the Meucci family made Havana their home. They found the warm and friendly nation a place for new and wonderful opportunities. Sr. Meucci pursued numerous experimental lines of research while living in Havana, developing a new method for electroplating metals. This new art was applied to all sorts of Cuban military equipment, Meucci gaining fame and recognition in Havana as a scientific researcher and developer of new technologies.

Several special electrical control systems were designed by him specifically for stage production in the Teatro Tacon, the Havana Opera. Electrical rheostats served the safe and controlled operation of enclosed carbon arclamps. Mechanical contrivances hoisted, lowered, parted, and closed heavy curtains. The automatic systems were a wonder to behold.

A young and dreamy romantic, Meucci found the beauty of theater work quite entrancing and inspirational. There, dreams became realities, if only for the short time during which hardened pragmatism was suspended. Fantasy and wonder were magickal liquids which perfumed the soul and opened the mind’s eyes. As in childhood, one could receive the elevating epiphanies of revelation necessary for discovering unexpected phenomena, and for developing unequalled technologies.

The decision to move to Havana was indeed a good one. Genuine acceptance, and loving recognition added joy the lives of the bittersweet exiles. Meucci’s wife was often amused by his more outlandish inventive notions. But, as their stay in Havana continued, she scolded that he had better develop something solidly practical on which to "make a living".

A long time fascination with physiological conditions and their electrical responses, Meucci was prompted to begin study of electromedicine. With just such a practical view in mind, he established and maintained an experimental electromedical laboratory in backrooms of the Opera House. Investigating the art of "electro-medicine", as popularly practiced throughout both Europe and the Americas, Meucci investigated the curative abilities of electrical impulse. Applying moderate electrical impulses from small induction coils to patients in hope of alleviate illness, Meucci learned that precise control of both the "strength and length" of electrical impulse held the true secret of the art.

As viewed by Meucci, pain and certain physical conditions were treatable by these electrical methods provided that very short impulses of insignificant voltage were employed. Impulses of specific length and power were necessary to rid suffering patients of their pain. In addition, Meucci imagined that tissue and bone regeneration could be stimulated by such means.

What really intrigued Sr. Meucci was the length of impulse time involved in body-applied electricity. To this end, he developed special slide switches which were capable of specifying the impulse length. It was possible to slide a zig-zag contact surface over a fixed electrical source. By varying the spacings between such slide contacts, Meucci could mechanically generate very short electrical impulses.

Rheostats could also be employed to control the current intensity. By the employment of these two control features, he was able to apply the proper impulse "strength and length". Meucci wished to chart a specific impulse series which would neutralize each specific kind of pain or illness. Developing catalogues of electrical impulse cures was his real aim. Such a technology, if developed thoroughly, could arm medical practitioners with new curative powers.

Sr. Meucci applied continual experimental effort toward these medical goals. He often applied these same impulses to theater employees and stage artists alike. These people came to regard such electric cures as definitive. Meucci’s method was known to reverse conditions completely. He paid special attention to the placement and size of electrodes on the body. Tiny point-contacts were often held to the body at specific neural points, effecting their analgesic effects. He was especially careful with "shock strength", applying only millivolt surges to his patients. Pain could be gradually made to retreat by the proper impulse administration.

Meucci had already developed fine rheostatic tuners for limiting the output power of his electrical device. He always applied the current to his own body in order to give completely "measured" electro-treatments. In this manner he was able to judge the parameters more personally and responsibly. It was his habit to administer treatments of this kind to his ailing wife, Esther. Crippling arthritis was becoming her personal prison, and Sr. Meucci wished to cure her completely of the malady. Watching and praying through until the dawn, Antonio struggled to perfect a means by which cures could be effected with selective impulse articulation.

As with each of Meucci’s developments, the fulfillment of his advanced medical ideas are found throughout the early twentieth century. Each researcher in this field of medical study employed very short impulses of controlled voltage to alleviate a wide variety of maladies. Independently rediscovering the Meucci electro-medical method throughout the early twentieth century were such persons as Nikola Tesla, Dr. A. Abrams, G. Lahkovsky, Dr. T. Colson. Each developed catalogues by which specific impulses were methodically directed to cure their associate illness. Each researcher developed a method for applying impulses of specifically controlled length and intensity to suffering patients, effecting historical cures.

More recently, several medical researchers have employed impulse generators to effect dramatic bone and tissue regenerations. They affirm that human physiology responds with rapidity when proper electroimpulses are applied to conditions of illness. These were closely regarded by government officials, eager to regulate the new science.

Most medical bureaucrats, fearing the elimination of their own pharmaceutical monopolies, sought opportunity to eradicate these revolutionary electromedical arts. Upton Sinclair obtained personal experience with these curative systems and the physicians who devised these methodologies. He championed their cause in numerous national publications with an aim toward exposing those who would suppress their work.

Sinclair pointed out the social revolution which would necessarily follow such discoveries. He was quick to mention that proliferations of new technologies would not come without a dramatic battle. Fought in the innermost boardrooms of intrigue, Sinclair underestimated the ability of regulators to eradicate technologies of social benefit.

This notable literary personage wrote extensively on the work of Dr. Abrams, who was later vilified by both the FDA and the AMA. An outlandish national purge quickly mounted into a fullscale assault on these methods. But this is a story best told in several other biographies. Meucci’s electromedical methods would soon be transformed into a revolutionary means for communicating with others at long distances.

SHOCK

The most central episode of Meucci’s life now unfolded. It was to be a serendipity of the most remarkable kind. Throughout his later years, Meucci recounted the following story which occurred in 1849, when he was forty-one years of age. A certain gentleman was suffering from an unbearable migraine headache. Since it was known to many that Meucci’s electromedical methods possessed definite curative ability, Sr. Meucci’s medical attention was sought.

Meucci placed the weak, suffering man on a chair in a nearby room. His weakened condition inspired an easy pity. Antonio had already felt the thorns of his beloved wife’s pain. Her eyes, like the man before him now, begged for the cure which lay hidden in mystery. Carefully, caringly, Antonio now sought to ease this man’s suffering.

In this severe instance, Meucci placed a small copper electrode in the patient’s mouth and asked him to hold the other (a copper rod) in his hand. The electro-impulse device was in an adjoining room. Meucci went into this room, placed an identical copper electrode in his own mouth, and held the other copper electrode to find the weakest possible impulse strength. Meucci told his patient to relax and to expect pain relief momentarily, making small incremental adjustments on the induction coil.

Migraines of severe intensity characteristically produce equally severe reaction to the slightest irritation. The man being now highly sensitive to pain, Meucci’s insignificant (though stimulating) current impulses were felt. The patient, anticipating some horrible shock, cried out in the other room with surprise at the very first slight tickle.

Momentarily, Meucci forgot the hurtful sympathy which he naturally felt in assisting this poor soul who sat across the hall. His focussed attention was suddenly diverted as an astounding empathy manifested itself: he had actually "felt" the sound of the man’s cry in his own mouth! After absorbing the surprise, he burst into the adjoining room to see why the man had so yelled. Glad the poor fellow had not run out on him, Meucci replaced the oral electrode of his suffering patient and went into the other room to perform the same adjustments...through closed doors this time. He asked the gentleman to talk louder, while he himself again held the electrode in his mouth.

Once more, to his own great shock, Meucci actually heard the distant voice "in his own mouth". This vocalization was clear, distinct, and completely different from the muffled voice heard through the doors. This was a true discovery. Here, Antonio Meucci discovered what would later be known as the "electrophonic" effect.

The phenomenon, later known as physiophony, employs nerve responses to applied currents of very specific nature. As the neural mechanism in the body employs impulses of infinitesimal strengths, so Meucci had accidentally introduced similar "conformant" currents. These conformant currents contained auditory signals: sounds. The strange method of "hearing through the body" bypassed the ears completely and resounded throughout the delicate tissues of the contact point. In this case, it was the delicate tissues of the mouth.

Each expressed their thanks to the other, and the relieved patient went home. The impulse cure had managed to "break up" the migraine condition. Meucci’s reward was not monetary. It was found in a miraculous accident; the transmission of the human voice along a charged wire. In these several little experiments, Meucci had determined and defined the future history of all telephonic arts.

VOICES

Excited and elated Antonio asked certain friends to indulge his patience with similar experiments. He gave individual oral electrodes to each and asked that his friends each speak or yell. Meucci, seated behind a sealed door, touched his electrode to the corner of his mouth. As each person spoke or yelled, Meucci clearly heard speech again. Internal sound reception in the very tissues of the mouth. An astounding discovery.

Without question, Meucci’s most notable discovery in telephonics is physiophony. Meucci did not foresee this strange and wonderful discovery. Think of it. Hearing without the ears. Hearing through the nerves directly! The implications are just as enormous as the possible applications. Would it be possible for deaf persons to hear sound once again? Meucci knew it was possible.

His first series of new experiments would seek improvement of the electrophonic effect. To this end Meucci designed a preliminary set of paired electrodes. The appearance of these devices was strange to both the people of his time and those of own. Each device was made of small cork cylinders fitted with smooth copper discs. Designed as personalized transmitters, each person was to place their own transmitter directly in the mouth! The other electrode was to be hand-held.

Meucci verified the physiophonic phenomenon repeatedly. Upon experiencing the now-famed effect, visitors were awed. Furthermore, it was possible to greatly extend the line length to many hundreds of feet and yet "hear" sounds. The sounds were clearly heard "in the nerves" with a very small applied voltage. Sounds were being deliberately transmitted along charged wires for the first recorded time in modern history.

The auditory organs were not in any way involved. Meucci discovered that oral vibrations were varying the resistance of the circuit: oral muscles were vibrating the current supply. Spoken sounds were reproduced as a vibrating electric current in the charged line which can be sensed and "heard" in the nerveworks and muscular tissues.

With very great care for obvious injuries, it is possible to reproduce these remarkable results to satisfaction. The voltages must be infinitesimal. When properly conducted through the tissues, sounds are heard near the contact point the body. No doubt, the impulsed signal reproduces identical audio contractions in sensitive tissues. This is one source of the sounds internally "heard". Nerves actually form the greater channel when impulses are arranged properly, directly transmitting their auditory contents without the inner ear.

Physiophony is Meucci’s greatest discovery, one which he should have pursued before also developing mere acoustic telephony. Twenty-five years later in America, an elated Elisha Gray would rediscover the physiophonic phenomenon. He would develop physiophony into a major scientific theme. Long after this time, these identical experimental demonstrations conspicuously appear in Bell’s letters; copying the identical experiments taken first from Meucci, then from Gray, and Reis.

During the early twentieth century, music halls for deaf persons were once found in certain metropolitan centers. These recital halls enabled nerve-deaf persons to hear music through handheld electrodes. Modifying the appliances in order to allow considerable freedom of movement, several such places allowed deaf people to dance. Holding the small copper rods, wired to a network on the ceiling, musical sounds and rhythms could be felt and heard directly. Physiophony, more recently termed "neurophony" holds the secret of a new technology. Physiophony, rediscovered of late, facilitates hearing in those afflicted with nerve-deafness.

Meucci discovered two distinct forms of vocal communication: physiophony and acoustic telephony. Meucci’s next experiments dealt with the development of a means for separating the physiophonic action from the human body entirely. He developed working systems to serve each of these modes, with primary emphasis on acoustic telephony. Replacing tissues of the mouth with a separate vibrating medium required extending the cork-fixed electrodes.

Meucci coiled thin and flexible copper wire so that it could freely vibrate in a heavy paper cone. Once more, Meucci varied the experiment. This time his own oral electrode would be enclosed in a heavy paper cone. Again each subject was asked to talk into the first cone-encased electrode as Meucci listened at the other terminal. Each time, speech was heard as vibrating air. This was his first acoustic transmitter-receiver.

Meucci wrote up all these findings in 1849...when Alexander Graham Bell was just 2 years old. Living in Havana at the time, Meucci conceived of the first telephonic system. He imagined that American industry would allow infinite production of his new technology. A telephonic system would revolutionize any nation which engineered its proliferation.

CANDLES

Freedom doors were not swung open in wide and unconditional welcome for Europeans during the latter 1800’s. Strict immigration laws forbade Europeans from even entering New York Harbor. It was more difficult, if not impossible, to find employment. New arrivals in America faced difficult, almost inhuman conditions. No support systems existed in the land of free-enterprise. No catch-nets for failed attempts in the land of the free.

True and unresisted freedom was reserved only for the upper class, who had already begun regulating and eliminating their possible competitors. Every means by which that prized upper position might be usurped was destroyed. Forgotten discoveries and inventions flowed like blood under the heavy arm of the robber baron.

The "New World" was not anxious to welcome these people. Discrimination against European immigrants went unbridled, unrepresented, and unchallenged. When American doors finally did open, there were no sureties for those who came to work and live in the New World. There was no promise, no meal, no housing, no job, no emergency support. To be in America meant to be on your own in America.

Prejudice against the "foreigners" was vicious during this time period. Immigrants who imagined a better life to the northlands would be sadly disappointed at first. Many of these newcomers preferred the temporary pain of atrocious city ghettoes simply because their eyes were on the future.

Europeans arriving in America came with trades and skills. Master craftsmen and technicians in their Old World guilds, these "unwelcomed" eventually won the hardened industrial establishment with their good works, many of them later forming the real core of American Industry. It is not accidental that Thomas Edison hired European craftsmen exclusively. In less than two generations the children of these brave individuals became leaders of their professions, giving the leukemic nation its periodically required red blood.

Established families despised the newcomers, who were regarded first with dread, then with resentment, and finally with a firm resolve. After ruthless campaigns by bureaucrats and moguls to eliminate the foreign presence in North America, wealthy puritanical antagonists sought the supposed surety of legislation to achieve elitist isolation. Neither cultivated nor creative, this ability to manipulate the tools of liberty for the sake of domination became a theme which continually stains their history. The unbridled and impassioned expansionism of these "foreign people" was so threatening to the impotent bureaucrats that legislation was installed for the expressed purpose of limiting their unstoppable movement. Sure that these were in fact the feared usurpers of a young and recently consolidated Republic, financiers impelled legislators to create a "middle class" economic stratum which has remained in force to this very day.

Bound to a life of tireless work and taxations, the children of immigrants no longer question the barriers to limitless personal achievement. While a very few wonder why their frustrations rarely allow escape into the true individual freedom of which America boasts, most simply satisfy themselves with banal consumer temptations.

Nevertheless, the "American" explosion in music, art, crafts, and technological arts followed the immigrants wherever they were forced to flee. When Antonio and Esther Meucci arrived in New York City, he was now forty-two. They made their home near Clifton, Staten Island.

Clifton was once a picturesque little town, nestled on a rocky ridge and surrounded by babbling brooks and lush forests. The year was 1850. The Meucci’s acquired a large and spacious house, filled with windows. Golden bright sunlight flooded the home in which Antonio devised the technology of the future. The rooms contained numerous pieces of striking art nouveau furniture which Meucci himself handcrafted. A beautiful four octave piano and several of these furniture pieces yet remain, the house itself having been declared a national monument.

His poor wife, now crippled completely, was confined to their second floor bedroom. It was there in Old Clifton that Sr. Meucci developed his "teletrofono". The device was successively redesigned and improved until several distinct and original models emerged. Mundane needs being the primary necessity, Meucci developed a chemical formula for making special chemically formulated candles and opened a small factory for their production. His smokeless candles earned a moderate income by which the small family could maintain their place in the New World. Throughout the long years to come, he also supported countless others who were in need.

He patented this smokeless candle formula, along with several other chemical processes related to his small industry. Soon, Antonio found that his candles were sought by neighbors, parish churches, and small general stores. He therefore took his devotions, and went into production of the same. Marketing the product locally, he was now again able to supply his experimental facility. This was his encouragement. The inventions began flowing again like rich red wine.

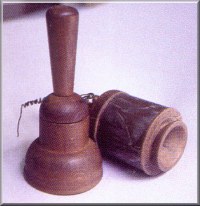

Meucci installed a small teletrofonic system in his Clifton house, as he had done in Havana. Esther Meucci was now completely crippled with arthritis. Connecting his wife’s room to his small candle factory, Antonio could now speak throughout the day with his wife. The system lines were loosely wrapped up and around staircase banisters, through halls, across walls, and finally spanned the long distance to the factory building, naturally running slack in several locations.

Meucci made sure that the lines did not run tight in order to prevent wire stretching and cracking during winter seasons. In every model aspect, Meucci’s system was the prototype. Everyone of his surrounding neighbors had become personally familiar with his system, having been allowed to try "speaking over the wire."

Meucci and his wife took boarders from time to time in order to afford minimum luxuries...the luxuries of ordinary people. When Garibaldi was exiled from Italy as an insurrectionist, he sought out Meucci. A small factory was established near his home for the manufacture of his chemically treated candles.

With this, his sole and sturdy financial source, Meucci continued his other beloved experiments. He had already established and regularly used several teletrofonic systems throughout his home and factory by 1852. Both he and Garibaldi walked, hunted, and fished in the lush greenery and flowing flowered hills of old Dutch Staten Island.

Each new teletrofonic design eventually was added to a growing collection box in the timber lined cellar. Improved models were made and brought into the general use of his system. With these modified devices it was effortless to communicate with his ailing wife, employees, and friends. Distances posed no problem for Meucci. His system could bring sound to any location. Numerous credible witnesses actually used his remarkably extensive telephonic system across the neighborhood. One such highly credible witness was Giuseppe Garibaldi himself.

Garibaldi was welcomed to live with the Meucci family in their modest Staten Island home for as long as he wished. Garibaldi, Meucci, and his wife vanquished sorrow and poverty with faith, hope, and love expressed in a myriad of ways. Each supported the other in the struggle against indignity, accusation, outrage, and all the particular little alienations imposed upon them. The Meucci household not unaccustomed to the deprivations through which character is developed.

Both Srs. Meucci and Garibaldi continued manufacturing candles and other such products of commercial value, supporting themselves and the needs of others in the new land. Frequent financial crisis never deterred his dream quest. Never did such reversals place a halt on Meucci’s laboratory experimentation or any of his devoted attentions.

As it happens in the course of time, new changes bring fresh opportunities and joys to lift tired hearts. The sun rose in the little windows after a long winter’s dream. An old friend from Havana came to visit Meucci and his wife. Carlos Pader wished to know whether Meucci had continued experimenting with his now famous "teletrofono".

Pader was shown the results, but Antonio confessed the need for new materials. Both Sr. Pader and another friend, Gaetano Negretti, informed their friend Antonio that there was an excellent manufacturer of telegraphic instruments on Centre Street in Manhatten. And so, Sr. Meucci was introduced to a certain Mr. Chester, a maker of telegraphic instruments.

Mr. Chester was an enthusiastic and friendly tradesmen. He enjoyed speaking with Antonio. The two shared their technical skills in broken dialects. Meucci was always welcomed there on Centre Street. Meucci visited this establishment on several occasions to purchase parts and observe the latest telegraphic arts. It was here that Meucci "gained new knowledge". He set to work, purchasing materials for new experiments. New and improved teletrofonic models began appearing in the neighborhood.

Meucci was methodical, thorough, and attentive to the unfolding details of his experiments. Meucci kept meticulous notes; a feature which later worked to vindicate his honor. He worked incessantly on a single device before making any new design modifications. Meucci’s creative talent and familiarity with materials allowed him to recognize and anticipate the inventive "next move". In observational acuity, inventive skill, and development of practical products he was unmatched.

Thomas Edison, after him, most nearly imitated Meucci’s methods. Meucci searched by trial and error at times when reason alone brought no fruit. It was, after all, an accident which revealed the teletrofonic principles to him. Providence itself in action.

TELETROFONO

Meucci methodically explored different means for vibrating electric current with speech. From 1850 to 1862 he developed over 30 different models, with twelve distinct variations. His first models utilized the vibrating copper loop principle which he discovered in Havana. Paper cones were replaced with tin cylinders to increase the resonant ring. He experimented with thin animal membranes, set into vibration by contact with the vibrating copper strip. This model begins to resemble the familiar form of the telephone as we know it.

Meucci wrapped fine electromagnetic bobbins around his copper electrodes, increasing vocal amplitudes considerably. In a second series, he explored the use of magnetic vibrators. A great variety of loops, coils, soft-iron bars, and iron horseshoes appear in Meucci’s successive designs. These latter models gave amazingly loud results. In addition, Meucci’s diagrams reveal experimentation with both separate and "in-line" copper diaphragms. These latter operated by the yet to be discovered "Hall Effect", where current-carrying conductors vibrate more strongly in magnetic fields produced by their own currents.

While power for his early teletrofonic system was derived from large wet cell batteries in the basement, Meucci made a pivotal discovery, discovered when he grounded his lines with large dissimilar metal plates. Suddenly, his system operated as if large batteries had been added to the line. Meucci disconnected the basement batteries and the system continued to operate, powered by ground currents alone.

This use of buried dissimilar plates repeatedly appears throughout early telegraphic patents. The actual devices by which this astounding electrification of lines was established were called "earth batteries". Several significant individuals made remarkable discoveries while developing earth batteries throughout the latter 1800’s. They found that the earth batteries were not really generating the power at all.

Earth batteries tap into earth electricity and draw it out for use. Some telegraphic lines continue to operate well into the 1930’s with no other batteries than their ground endplates. Certain systems continued using their original earth batteries without replacement in excess of 40 years!

Earth batteries are intriguing because they seem never to corrode in proportion to the amount of electrical power which they generate. In fact, they scarcely corrode at all. Exhumed earth batteries showed minimal corrosion. A mysterious self-regenerative action takes place in these batteries, a phenomenon worthy of modern study.

Like Thomas Edison after him, Meucci was a master of practical chemistry. Numerous of his processes remain unused to this day. He developed strange chemical coatings; using saltwater, graphite, soapstone, wax, muriatic acid, asbestos, sulfur, and various bonding resins to treat wire conductors. Wire lines, specially treated by Meucci, had current rectifying abilities. These absorbed and directed both terrestrial and aerial electricity into the line, a one-way charge valve. Technically what he created is a large surface area diode.( Moray)

When these specially coated wires were elevated, Meucci enhanced the absorption of "atmospheric electricity" into his system. Prevented from escape by chemical coatings, a steady stream of aerial charges were absorbed into the wire line. He succeeded in powerfully operating his system with "aerial electricity" alone.

Meucci now freely used aerial and earth electricity to power his teletrofonic system. In addition, he discovered that the latent power in strong permanent magnets could amplify speech with very great power. When coupled with energy derived from the ground, Meucci found that true amplifications could be effected. Meucci found that vocal force being sufficiently powerful to produced amplified reproductions at great distances in certain of his models which utilized magnetite "flour".

Sound-responsive soft iron cores were replaced with lodestone and surrounded by various powdered core composites developed in Meucci’s laboratory. Lodestones, surrounded with cores of flour-fine iron powders, produced enormous outputs. Meucci used exceedingly fine copper windings. The vocal range of these magnetic responders was considerable when made in Meucci’s own unique design.

Clear, velvety speech was communicated with great power in these fine-powder core designs. His use of flour-fine magnetite powders produced the world’s first ferrites; composites of iron, zinc, and manganese later used in radiowave transformers.

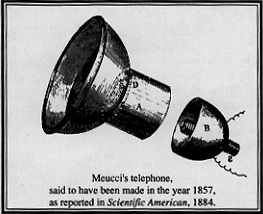

His teletrofoni were now fully formed, handheld devices of some weight. Surviving models from his system resemble those much later manufactured by Bell telephone. They are cup-shaped, wooden casings...handheld transmitter-receivers. One speaks into the device, and then listens from the same for replies. Meucci’s diagrams, notebooks, and models prove his priority over all the historically successive telephone designs.

In addition, Meucci used diaphragms which conducted the current which vocalizations could modulate. He developed remarkable graphite-salt coatings to enhance the electrical conductivity of his responder diaphragms, preceding Edison’s carbon button microphone by a full 24 years!

TRANSOCEANIC

In addition to his existing system, Meucci conceived of entirely new directions in communication arts. His mind turned toward the sea...and to transoceanic teletrofonic communication. Meucci tested the idea that seawater could actually replace telegraph cables, bizarre as it must yet sound. His notion would be termed "subaqueous conduction wireless". Others had achieved moderate results across limited waterways. Sommering, Lindsay, and Morse each sent weak telegraph signals across streams. Meucci envisioned the whole Atlantic as a possible reservoir for the transmission of telephonic signals.

His experiments took him down to the Staten Island seashore with his teletrofono, batteries, and large plates of both copper and zinc. The dissimilar metal plates were submerged quite a distance from each other. Vocal messages spoken into the sea were electrically retrieved by a teletrofonic apparatus connected to an equivalent arrangement of widely separated, water-immersed plates on an opposed part of the distant shore. The signals were clearly heard.

Most engineers will object that these experiments could not sustain vocal communications across great distances. They will say this because transmitter power should be so dispersed that no intelligible signal could ever be retrieved. The experiment having been tried across short distances actually works. The most amazing rediscovery concerns the signal-regenerative ability of seawater. Seawater requires only an infinitesimal transmitter current in order to achieve strong signal exchanges.

The submerged plates themselves generate sufficient current to operate the teletrofonic system without batteries. Electrical signals do not diminish in seawater as theoretically expected. When Meucci spoke of transoceanic communications he was not exaggerating. Seawater seems to be a self-regenerative amplifier of sorts. The addition of a carrier frequency (an electrical buzzer) would pitch the signals toward a higher range, granting more signal focus.

Sir William Preece duplicated these experiments for telegraphy across the English Channel in the early 1900’s. Their developing success was eclipsed by the appearance of aerial wireless. Some researchers have interpreted the work of G. Marconi to be a blend of Meucci conduction telegraphy and aerial wireless. While purists protest, it is intriguing that Marconi would later actually resort to mile-long submerged copper screens for transoceanic communications. The submerged copper screens acted as a "capacitative counterpoise", following his equally long aerials...out to sea.

Several segments of these Marconi aerial-screen systems have been located by investigators, both in New Brunswick (N. Jersey) and in Bolinas (California). The Marconi "bent-L" aerial system differs from Meucci’s design only in that it utilized several hundred thousand watts of VLF currents. In effect, Marconi employed Meucci conduction wireless in his early transoceanic systems.

Meucci became prolific when designing these maritime inventions. It was told him that a certain deep-sea diver, having once distinctly heard a steamship engine while performing a salvage operation, was told (on resurfacing) that the ship was fully forty miles away! This phenomenon so impressed Meucci that his mind turned toward the use of his teletrofono in deep-sea communications and offshore ranging.

His notion was truly original, involving this submerged plate system for wireless vocal communication. The use of short aerial rods projecting from the diver’s helmet formed the very first "aerials". Divers could maintain communications with their surface companions without interruption if such teletrofonic aerials and internally housed responders were installed in their helmets. Sealed aerial rods (one foot or less in length) would protrude out from the helmet, forming the wireless link; an invention truly worthy of Jules Verne! Transmissions and receptions would occur through the remarkable conductive-regenerative ability of seawater to conduct electro-vocal signals.

Of chief concern in Meucci’s mind was the establishment of solid maritime wireless communications systems. He designed several systems intended to aid harbor approach and navigation during times of limited visibility. Clusters of tone-transmitters (positioned as fixed stations or anchored as buoys) could wirelessly communicate danger or safety to sea captains equipped with onboard listening devices. Both landmark stations and onboard responders would communicate through seawater with submerged metal plates. These plates would be fixed in position at some depth; much below each landmark and right under the ship hull.

Navigators would be guided into safe harbor by following a specific tonal signal, and avoiding the selected danger tones. These tones would be subaqueous transmissions...true tonal beacons. Navigators were to carefully listen for guide-tones while entering a harbor. Pilots could locate their offshore position with precision by simply listening for the designated subaqueous tonal beacons.

Position could be triangulated by comparing tones and their relative volumes. Tones could be determined by comparison with a small on-board receiver containing tuning forks. Maps could mark these tonal-stations and pilots could rely on their presence. Meucci wished to eradicate the blinding dangers of fog and storm for sailors. Meucci accurately foresaw that an entire corps of maintenance operators would find continual employment in such worthy service.

In all of this, Meucci actually anticipated the LORAN system by a full seventy-five years! In the years before radio pierced the night isolation of shipping, ships maintained tight commonly used sea-lanes when far from coastlands. Mid-oceanic collisions were not uncommon. Meucci conceived of systems by which ships could transmit warning beacons toward one another while out at sea. Helping to avoid such mid-ocean disasters, sensitive compass needles would detect passing ships. Plate-pairs would be poised beneath the ship’s hull in the four cardinal directions. Relays could detect ships, responding with loud alarms.

In addition, ships could launch teletrofonic currents in the direction of specific approaching or passing ships, establish continual vocal contact. Meucci accurately foresaw the development of new maritime communications corps, anticipating those wireless operators who would later be called "sparks" by their crew mates.

EXPLOSIONS

Lack of funding alone prevented Meucci from making large scale demonstrations of his revolutionary systems. In addition, prejudices associated with his nationality prevented New York financiers from even knowing of his activities. Meucci turned to his own patriots for help.

Confident in the both the originality and diversity of his teletrofonic inventions, Meucci was now sure that he could convince Italian financiers to help commercialize the Teletrofonic System; not in America, but in Italy. Meucci (now fifty-two years old) set up a long distance demonstration of his system in 1860 in which a famous Italian operatic singer was featured. His songs being transmitted across several miles of line, Meucci attracted considerable attention. Featured in the Italian newspapers around New York City, he indeed attracted the attentions of financiers.

Sr. Bendelari, one such impresario, suggested that full scale production of the teletrofonic system begin in Italy. He travelled to Italy with drawings and explanations of what he had seen and heard. Contrary to the hopes of all, Sr. Bendelari found it impossible to interest financiers in the teletrofonic system. Civil wars distracted the ordinarily aggressive Italian development of all such new technology.

Italian production of the teletrofono having never begun, Meucci became extremely embittered over both the incident and his own circumstance in America. American financiers were no better. Most contemporary Americans who had any "practical financial sense" at all could not believe that any mechanical device could actually transmit the human voice. They were far less interested in investing their fortunes toward developing systems which they considered fraudulent.

On sound advice from sympathetic compatriots, Meucci was warned never to bring anything to the American industrial concerns without first protecting himself by legal means. Before Meucci could dare bring his models the short ferry trip to Lower Manhattan to the developers, he needed a patent. Patents have never been cheap to obtain, this the regulator’s tool. Even in those days, a patent cost a full two-hundred and fifty dollars.

Exorbitant costs being established for the financier’s benefit, no independent inventor-novice could ever become an independently successful competitor without "financial assistance".

Meucci settled the matter by obtaining a caveat, a legal document which was considerably cheaper than the patent. Antonio could now only afford a caveat, a legal declaration of a successfully developed invention.

The caveat describes an invention and shows the time-fixed priority of an inventor’s work. Meucci had models as well as the legal caveat. His caveat would stand in court, bearing the official seal, a registry number, and the signatures of witnesses. The Meucci caveat was taken in 1871, when he was 63 years old.

While travelling from Manhattan to Staten Island, Meucci was nearly killed when the steam engine of the ferry exploded. He survived this explosion in some inexplicable miracle, severely burned and crippled. While he languished in a hospital bed, his wife sold his original teletrofono models for the small sum of six dollars in order to pay for his expenses.

These models were sold to one John Fleming of Clifton, a secondhand dealer. Attempting to repurchase these models, he was informed that a "young man" had secured the models. Unable to locate the purchaser, Meucci was devastated. He suddenly felt that his own creation was already taking on a life of its own...fleeing away from him, out of control.

Growing desperate with thoughts of his own growing age and poor condition, Meucci now pursued the issue of commercializing his invention without restraint. In 1874 Meucci met with a vice-president of the Western Union District Telegraph Company, a certain W.B. Grant. Meucci described his "talking telegraph" and the complete system which was now operational. Meucci requested a test of his teletrofoni on one of the Telegraph Lines and was promised assistance and cooperation.

Mr. Grant appeared in earnest, engaged Meucci for a long while, and requested Meucci to leave his models. Meucci did so, being encouraged that he would be contacted very shortly for the test run. Hours of waiting became days. At this point, Meucci attempted to contact Grant again. The vice president could "never be found". Meucci continued visiting Western Union in hopes of reaching Grant and performing the required long-distance tests as promised him originally.

Meucci became bitterly angry over this betrayal of trust. The duplicity involved in the act of such unprofessional denial so exposed the fundamental methodology of American business that he wondered why he had ever left Cuba. So infuriated was he that he maintained a vigil at the Union Office, becoming an annoying eyesore. White haired, bearded, and bowed over with age, Meucci was viewed as a harmless old fool by younger, more aggressive office workers.

Adamant to the last, Meucci finally and loudly demanded the return of his every model. He was then very curtly informed that they "had been lost". Grant had passed these devices onto Henry W. Pope for his professional opinion on the exact working of the devices, forgetting the issue completely in the course of a business day. The monopoly had beaten another victim. He stormed out.

The path which the Meucci models took inside Western Union has been traced. The models periodically kept appearing and disappearing in the electrical research labs of Western Union, revealed through the written studies of several curious individuals. The models were transferred among several engineers as successive new electrical directors were installed. Each examined the models in complete ignorance. Lacking introductory explanations, no one comprehended what the weighty wooden cups could do when electrified.

Franklin L. Pope, friend and partner with young Thomas Edison at the time, was given the models by his brother. Together Pope and George Prescott could not understand the nature of the devices, putting them into a storage area in Western Union. This seems to be the last mysterious repository of Meucci models. Given in trust years before, the models sat in the dustbins of Western Union. Lost science.

The true history of telephonics begins with Meucci. Others, far younger, were raised in an atmosphere which was enriched by Meucci’s developments. Phillip Reis noted the telephonic abilities of loosely positioned carbon rods through which flowed electrical currents. His primitive carbon microphone was later stolen by a vengeful Edison, who was in search of some means for both "breaking" the Bell Company’s hold on telephonics, and saving his own financial record with Western Union Telegraph.

Meucci led the way long before others. It must be mentioned that both Gray and Reis were independent and equally great discoverers who each, though antedating Meucci by some 20 years, actually predated Bell by at least 10 years. Some have suggested that, as Bell was encountering great difficulty in developing his own telephonic apparatus, these same models were given to him for the expressed purpose of speeding the race along.

Western Union would engage Edison to "bust" the Bell patent in later years. Edison’s invention of the carbon button telephonic transmitter was an inadvertent infringement of Meucci’s earliest responder designs. The industrialization of the telephone revealed the repetitious and convoluted infringement of Meucci’s every system-related invention. Bell’s own frantic rush to develop telephony had more to do with his need to "live up to" sizable investment monies given him for this research, and less with any true inventive abilities. The truth of this is borne out in considering Bell’s later work, involved in his frivolous failed "kite developments". Indeed, without the fortunate "assistance" by friends at the Patent Office, Bell would have succeeded in neither defeating Meucci’s caveat nor Gray’s electro-harmonic patent.

TELEPHONE SYSTEMS

Those who wished the implementation of telephony for financial gain, chose more controllable and less passionate individuals. Neither Meucci, Gray, nor Reis fit this category of choice. The Bell designs are obvious and direct copies of those long previously made by Meucci. The dubious manner in which the Bell patents were "handled and secured" speak more of "financial sleight of hand" than true inventive genius. The all too obvious manipulations behind the patent office desk are revealed in the historically pale claim that Bell secured his patent "15 minutes" before Gray applied for his caveat. Today it is not doubted whether perpetrators of such an arrogance would not go as far as to claim "15 years priority".

Lastly, this fraudulent action denied the years-previous Caveat of Meucci, which "could never be found at all in the patent records" during later trial proceedings. No mind. Meucci is a legend. A name suffused by mysteries. The Meucci caveat remains to this day on public record. All subsequent telephone patents are invalid. Meucci bears legal first-right. No lawyer today will decline this recorded truth.

All other court actions taken against Meucci toward the end of his life was staged by both the corporate Telephone Companies and the Court itself for the expressed purpose of securing the communications monopoly. The complete and operational Meucci Telephonic System, witnessed and used by countless visitors and neighbors for equally numerous years before Bell, was well documented in both Italian and local papers of the day.

To read the transcript of the Meucci court battle waged around the now aged and infirm Meucci is to witness the fear which large megaliths sustain. Though Meucci was not able to afford the yearly renewal price of his caveat, his priority was damaging, otherwise they would not have taken such measures to examine him publicly. The Bell Company sought to minimize Meucci’s system by calling it nothing more than an elaborate "string telephone" in court proceedings, exposing themselves on several counts of fraud. Scientifically, this line of defense was unfounded. The obviously slack lines made the Meucci System incapable of conducting merely elastic vibrations with such clarity and amplitude. Moreover, the velvety rich tones received through these devices were far too modified, clarified, and loud to be "mere mechanical transmissions".

It was then hoped that the elderly gentleman would desist the entire crude process and give up. Meucci was publicly and ethnically labelled by leading journalists as "that old Italian, that old...candlemaker". Meucci maintained his ground to the consternation of the prosecuting attorney. Priority of diagrams, witnesses, working models...nothing could satisfy the predetermined judgement of the court.

To add insult to injury, Meucci’s character was vilified in the press. In numerous pro-corporate newspaper articles Meucci is referred to as "a villain...a liar...an old fool". Predetermined to satisfy the corporate megalith, a deliberate and shameful court examination had as its aim the eradication of Meucci and his claim of priority. This process would later become the normal mode of business operation when destroying competitive technologies. With no hope of financial reprise in sight, Meucci ceased the excessive court fees. This was precisely what the monopoly wished. The fact yet remains that Meucci was first to invent the system.

Throughout the years, Meucci’s name was not even mentioned in the history of telephonics. Closer evaluation of this true social phenomenon in "information control" reveals that communications history sources were controlled and principally provided in later years by Bell Labs to school text companies. They would ensure that the otherwise complex story was "straightened out".

It is also obvious that Meucci and his countrymen were never truly "embraced" by the American establishment until they took deliberate action. To the very end of his life, Meucci simply and elegantly maintained his serene statements in absolute confidence of the truth which was his own. "The telephone, which I invented and which I first made known...was stolen from me".

The more important fact in these matters of intrigue is recognizing that discovery itself is no respecter of persons or indeed of nations. Discovery touches those who honor its revelations. Discovery is an inspiring ray whose tracings are never limited by laws, prejudices, unbelief, nation, ethnic group, or economic bracket.

LEGEND

Eager to maintain their ascendancy in the annals of corporate America, incredible odds were marshalled against the aged Meucci by The Bell Company. In this determined counsel, we see the singular insecurity which frightens all secure investments. In truth, no investment is ever secure, when once discovery is loosed on the earth. What corporations have always feared is discovery itself. It is an unknown. In attempts to capture discoveries before they have time to take root and grow, every corporate megalith employs patent researchers. Their job is to waylay new company-threatening inventions.

Inventors represent the true unknown. They are uncontrolled forces who truly hold the power of the economic system in their grasp. Were it not so, then corporate predators would not pursue them with such deliberate vehemence. No one can destroy an idea once it has made its appearance on earth. Discovery is neither controlled or eradicated by the powerful. Attempts at wiping out new technology mysteriously result in a thousand diversified echoes, moving in a thousand places simultaneously.

The biography of Antonio Meucci is suffused with the deepest of emotions. I have read the biographies of many great and forgotten science legends, yet have not found one whose pathos completely equals that of Meucci. Despite the manner in which the new world treated him, the dignity of this great inventor is silently mirrored in his every portrait. The face of Antonio Meucci is serene...the face of a saint.